- Home

- Susan Warren

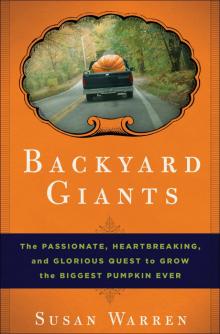

Backyard Giants Page 25

Backyard Giants Read online

Page 25

"You've always had a nice bottom, Joe," Mike Oliver added. Somebody had to say it.

Joe had not had such a great year in his pumpkin patch. The storm that had leveled his plants in July had been a major setback. But he'd had more success with something new. Joe had decided this year to try his hand at growing long gourds—baseball-bat-shaped fruit that grow from climbing vines. Growers competed to see how long they could grow these. The world record stood at 116 V% inches—more than 9 feet.

Joe built a 12-foot-tall trellis to support the vines and give the gourds plenty of room to hang. And he'd grown a gourd 126 Vz inches long, beating the old world record his first year trying. Joe had cut the gourd from the vine and taped it to a long board to stabilize it for transport. At the Frerich's Farm weigh-off, he'd have the gourd's length measured and officially certified. His giant pumpkins weren't much to crow about, but if nobody had grown a longer gourd that year, he'd have a shot at his own world record after all.

The Rhode Island team drove from patch to patch that Friday, loading pumpkins. It was slow work, and fraught with unexpected difficulties. At Norm Gansert's house, the loading crew found that he'd grown his pumpkins on the side of a steep hill. There was no way to set up the tripod or back in a truck. They had no choice but to use a tarp to manually haul an 800-pound pumpkin up the hill to the truck.

Backs were aching by the time the lifters arrived at Peter Rondeau's house. Peter was bringing his 1068 to the weigh-off, but he'd been fighting a problem with the stem the past few days. The skin around the stem was cracking and curling like old paint. But it wasn't rotting, and the pumpkin was still in good-enough shape to be weighed.

It was after 4 P.M. by the time all the pumpkins had been loaded and 5 P.M. by the time they arrived at Frerich's Farm to unload. David Frerich, the farm's owner, had decided to hold the weigh-off in the parking lot instead of in the grassy field next to the farm, which was still soggy from rain. Frerich ran the 200-acre farm and nursery with the help of his wife, Barbara. The couple hoped the weigh-off would be good publicity for their nursery business, which needed a boost after its worst year ever. The Frerichs specialized in decorative fall crops, growing squash, gourds, chrysanthemums, and 15 acres of field pumpkins—the jack-o'-lantern kind. Their mum business had done well—they had started the year with 30,000 pots of the colorful flowers and were down to just 4,000. "That's the only highlight to the whole season," Frerich said. The rains had delayed planting, so they'd been able to bring in only one good hay crop, instead of two. Disease ruined their tomato and cucumber crops. And the summer heat wave had stopped the pumpkin plants from setting fruit, decimating that year's yield. The Frerichs weren't alone—pumpkin crops all up and down the East Coast had been ruined, making it a lean fall for jack-o'-lanterns.

"I've talked to seventy-five-year-old guys and they say this is the worst year they've ever seen in their entire career," Frerich noted.

The Rhode Island pumpkins were unloaded and set in a line on the grass along the edge of the parking lot, just down from the pump kin catapult Dick had made one winter for David Frerich. The Frerichs entertained schoolchildren on field trips by loading little pumpkins into the catapult and launching them across an open field, where they landed with a splatter.

The Rhodies hovered protectively over their pumpkins, getting their first good look at the fruit off the vine. Peter leaned over his 1068 and slapped it hard with his open palm. Then he laughed self-consciously. He hadn't the faintest idea what he was listening for. "That's an art I haven't learned yet," he confessed to Joe. Joe gave the pumpkin a confident thump, more with the heel of his hand than with his palm. "Put your ear on that," Joe told him. "Feel that?" Thump thump thump. The pumpkin vibrated dully under his pounding. Peter's face looked blank.

"Slap it harder," Peter said.

THUMP THUMP THUMP.

"Can you tell any difference?" Joe asked.

"Not really," said Peter.

Ron was fussing over his pumpkin, concerned that the water bags were still full, which meant the pumpkin wasn't sucking up much moisture. He stood back, looking first at his own pumpkin, then at his dad's, then at his own again. The two 1068s were set side by side, just a few feet apart. It was the first time he'd been able to really compare them that way. To the eye, Dick's pumpkin looked slightly larger, but the tape measure showed Ron's to be bigger by a few inches. Both were pale orange and roughly the same shape—though they had distinctly different personalities. Ron's pumpkin was a sumo wrestler sitting back on fat haunches, muscled ribs bulging with veins, powerful shoulders surging forward around the stem. Dick's pumpkin was rounder, softer, nicer-looking, reclining on its blossom end like Great-Aunt Nellie resting in her favorite chair. Dick had named his pumpkin Mrs. Calabash. Ron had suggested calling it Durante, because of a slight hump on top reminiscent of comedian Jimmy Durante's famous big nose. Dick was a traditionalist, though. Pumpkins are females, the womb of the plant. So he'd borrowed from Durante's nightly sign-off, "Good night, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are."

"I think these two pumpkins could be within twenty-five pounds of each other," Ron concluded. "You never know. This one"—he ran his hands across the rough surface of his pumpkin—"on the blossom end and the stem end is solid meat. Now, like I've been saying, all I need is 3 percent heavy to hit fourteen hundred pounds."

That was Ron "the numbers man" talking. He had, of course, calculated the estimated weight of his pumpkin based on its OTT measurements: 1,367 pounds. And how much more it would have to weigh to break over 1,400 pounds: 3 percent more. And how much more it would need to break 1,500 pounds: almost 10 percent.

The problem with that, as Ron well knew, was that the bigger a pumpkin was, the less likely it was to go heavy, as recent history had proven. In fact, odds were far greater that it would go light. Witness Larry Checkon's estimated 1,700-plus pumpkin, which actually weighed 1,469, and the rumored 1,500-plus pumpkin from New York, which just the previous week had weighed less than 1,100. But neither had been grown from a 1068 seed.

"You know what," Ron said, snapping back to reality, "just to finish out the season, to get one to the scale—whatever it weighs, it weighs. But I've got a good shot going into tomorrow." Ron was swinging wildly now between the Dr. Jekyl of cautious optimism and the Mr. Hyde of crazy hope. "If I do what I did at Topsfield or better, then I have a good shot at Grower of the Year. And if it happens, it happens. But this was really just about me, proving to everybody that I can do this thing."

The daylight was fading fast, and the temperature was dropping. Ron fetched an armful of blankets and comforters from his truck and started tucking them around both his pumpkin and his dad's. None of the other growers bothered covering their pumpkins.

"It's going to get cold tonight," Ron explained.

"Mine is tough; it can take it," Joe cracked, getting a laugh out of the other growers. But Ron was dead serious. "You never know. Tonight is a harvest moon . . . You could get a frost."

"Naaah," Joe said. "Not with this wind. With a wind like this, you won't get a frost."

It was, indeed, very windy. And it was getting colder as night fell. The setting sun spackled the sky with a last gasp of electric blues and pinks. The Rhode Island mafia drifted together into a small circle, an instinctive gathering of the tribe. It was time to go, but they seemed to be having a hard time leaving their pumpkins. Dick was already thinking ahead to the next day's weigh-off. Ron would emcee the event, announcing the growers and the pumpkin weights. They had 45 pumpkins registered for the contest, and only one scale. Dick worried it would get tedious for the crowd, and he wanted to make sure Ron kept things interesting. One way to do that, he suggested, was to announce the awards for prettiest and ugliest pumpkin as the owners had their entries weighed. "Just tell them something like, 'Gee, that's an ugly pumpkin!' or however you want to ad-lib it, and then give them their award right then," he advised Ron.

Ron tucked his chin under and looked at his dad through his eye

brows with a son's patient skepticism. "Okay," he said. "I will."

Dick pressed on. "There has to be some excitement for the crowd," he insisted.

That got a rise out of the other growers. Excitement at a pumpkin weigh-off? "Ooooooooooooo!" the men all chorused breathily.

"And the crowd goes wild!" Peter said, cracking up everyone except Dick.

"Ah, come on," Dick said, throwing his hands in the air.

"Alright. Ready to get out of here?" Ron asked briskly, breaking it up. Nobody moved. Everyone fell silent. The mood shifted subtly. It was the end of the season. Finally. There was nothing to do now but wait for tomorrow. They didn't even have any pumpkins to go home to.

"Well, boys," Ron said after a short silence. "We've only got twelve more hours as GPC champions."

"Yeah," Dick said. "Ron is going to be laying in bed all night, saying, 'I hope my father doesn't beat me, I hope my father doesn't beat me.'" He paused while everyone laughed, then added with a grin, "And I'll be laying in bed thinking, 'I hope my son beats me, I hope my son beats me.' "

Pumpkin weigh-offs aren't your typical competition. Once the pumpkins are lined up at the scale, there's not a darn thing for the competitors to do. They can't run faster or jump higher or sing louder to improve their chances of winning. The race is already run. Their pumpkin will weigh what it weighs. It's just a matter of waiting to find out the number. Which makes pumpkin weigh-offs a little slow in terms of action and also torturously long and tension-filled for the growers who hope to win.

That may have been why Dick Wallace was more than a little cranky the morning of the weigh-off. His mood matched the long-sleeved black T-shirt he'd donned for weigh-off day, which was emblazoned with a picture of an evil-faced, flaming orange pumpkin against a background of crossed swords. No one blamed him for being out of sorts. By the end of the day, the Wallaces would either be winners or just a couple of schmucks who'd spent their whole year—again—trying to grow the world's biggest pumpkin.

The Rhode Island growers had arrived at Frerich's Farm before 9 in the morning to begin preparing for the 1 P.M. weigh-off. There was a lot of work to be done: setting up the scale, unloading pumpkins, decorating the podium, and erecting the magnificent new pumpkin-shaped scoreboard Joe Jutras had made only a few days before. Every grower was assigned a job, and Dick's was to check in contestants and make sure they were registered and had paid their membership and entry fees. He sat at a white folding table next to the podium, silently flipping through a stack of papers, an unmistakably antisocial look on his face. A bottle of champagne was at his elbow, waiting for the winner of the day's weigh-off. At the end of the table, Ken Desrosiers, the BigPumpkins.com Webmaster and SNGPG director, was setting up his computer equipment. He would be entering all the growers' data and the weigh-off results as each pumpkin went to the scale, for posting later on the Web site.

Ken couldn't help but notice Dick's sour mood. "Dick, you're not your normal self." Without even looking up, Dick grumbled something unintelligible. But then his good nature got the better of him. "I haven't been sleeping well lately," he explained. "I wake up at two thirty, three A.M. And then that's it. Night's finished. I can't get back to sleep."

The farm's parking lot was bustling with activity. Growers had already begun trickling in, and Peter Rondeau was busy directing the forklifts as they unloaded the pumpkins and began setting them in line to be weighed, smallest to largest. Joe, Steve Sperry, and Scott Palmer were constructing a frame for the big scoreboard that would serve as the backdrop for the afternoon's action, if only they could figure out how to get it to stand up at the back of the flatbed truck they were using for the weigh-off stage.

Ron had the jitters big-time, but he coped by going into manager mode. Rectangular, mirrored sunglasses concealed his eyes. He paced around the parking lot with his lucky orange jack-o' lantern T-shirt peeking out from beneath his long-sleeved denim SNGPG shirt, drifting from workstation to workstation to check on everyone's progress and then wandering away to make another call on his cell phone. He was worried the stage wouldn't be ready in time. He was worried the parking lot was too small and cramped for the weigh-off and the crowd. He was worried his pumpkin would go light—oops, no, scratch that. He refused to entertain the thought. He was actually more worried that the Ohio growers would have such a big pumpkin they'd be impossible to catch.

One mercy: The Ohio weigh-offs were starting in the morning. They should be finishing up about the time the Rhode Island weigh-off got underway. That meant Ron would know exactly what he was up against before his pumpkin went to the scale. Would he be trying to beat a new world record from Tim Parks? From Buddy Conley? From Quinn Werner? Someone had talked to somebody and the word was that Werner had arrived at the Ohio Valley weigh-off that morning with a giant bomb that could blow everybody away. And no one was counting out Port Elgin, Ontario. There could easily be a surprise waiting in Canada, which had claimed world records in 2004, 1998, and 1994.

By 11 A.M., a line of heavily laden pickup trucks had stacked up along the drive into farm, and two forklifts were humming and beeping nonstop as they ferried pumpkins to the parking lot.

Growers from across New England were lined up in front of Dick's table as he paged through his lists, looking less cranky now, focusing on his task. He had some help from Ed Giarrusso's wife, Rose, a cheerful woman who seemed more unabashedly excited to be there than any of the growers that morning. She'd been delighted when her husband had weighed in his first 1,000-pound pumpkin at Pennfield Beach the week before, and she was hoping he would have an even bigger one today. She beamed from her chair in an orange corduroy shirt, greeting the growers with infectious good spirits. Dick left the check-in to her and got up to attend to his favorite part of the ceremony: the awards. He'd been assembling the collection of ribbons and trophies since last year's weigh-off, and they would finally be put to good use today.

Dick tacked the ribbons in a row across the front edge of the truck-stage. They were as big as homecoming corsages, four-inch buttons surrounded with ribbons of black and green and orange and purple. He lined up the trophies along the top. Dick and Joe had cooked up an assortment of trophies and plaques, all topped with a ceramic or glass or plastic pumpkin, including one sitting on top of a toilet—the "Ugliest" prize.

Dick's mood lightened as he concentrated on the awards. The scoreboard was finally up and looking good. The day was bright and sunny, though very windy and a little cool. Dick had purchased a collection of decorative flags to mount around the stage. Now they were flapping and snapping colorfully in the brisk wind. The U.S. flag flew high above the scoreboard, right in the middle. A crowd was gathering. A few hundred people already were milling around the parking lot, with more arriving every minute. Spectators wove in and out of the giant pumpkins lined up at the edge of the lot, posing for pictures in front of their favorites. Children were impressed, but the adults were incredulous. "Look at these!" one woman said to her companion. "They're all different colors. They look fake!"

At 12:30 P.M., Ron directed the crowd over to a field behind the parking lot where a crane was waiting to start the weigh-off with a splat. It had become a popular feature at pumpkin weigh-offs in recent years to find creative ways to smash the big fruit as enter tainment. It made up, a little, for the tedium of the actual weighing. Most events simply dropped a pumpkin from a crane and let it splatter on the ground at the feet of the spectators. Some were more ambitious: the Terminator Weigh-off at the Chinook Winds Casino in Lincoln City, Oregon, climaxed with a 1,000-pound pumpkin dropped 8 5 feet onto a car.

The Frerichs had chosen the simple crane-to-ground drop, and the crowd, which had swelled to nearly 1,000, migrated obediently to the field to watch the spectacle. The people roared their approval as the pumpkin went into freefall, a bright orange spot against a blue sky, soaring through the air like Linus's mythic Great Pumpkin, except with more velocity. It shattered against the ground with a gratifyingly wet thunk, spreading gor

y chunks of pumpkin guts about and generating cheers, applause, and whistles from the delighted audience. Once the flying pumpkin was smashed, they quickly lost interest in it and drifted back to their spots in the bleachers. It was time for the weigh-off to begin.

Ron Wallace had never been what you would call a relaxed kind of guy, even on his calmest days. But that afternoon he was coiled so tight it seemed the slightest touch would send him springing like a jack-in-the-box. He picked up the microphone and stepped onto the podium his father had built. It was only about a foot tall and set right in front of the scale to keep Ron close to the action. Behind him loomed the stage, with Mike Oliver's two young daughters posted on either side of the scoreboard, like teenage Vanna Whites dressed in sweatshirts and jeans, with the youngest wearing a neon-orange wig.

Ron looked out over the parking lot to the crowd packing the bleachers at the opposite end. His sunglasses reflected the bumpy orange field of giant pumpkins stretched out before him. It was time to begin, and he had prepared a small speech. Ron did not have the zoom and zest of Jim Beauchemin, but he was perfectly comfortable in the spotlight.

"A few years ago people wouldn't have thought it was possible," he began. "They think of Rhode Island and they think of the 'Island State,' sailing—stuff like that. Giant pumpkins don't come to mind. But in the last few years a group of individuals has got together and we've fought and we're very proud of our accomplishments. Last year we were named the number-one weigh-off site for giant pumpkins in the world. We hope to retain our title today, but we're up against a tough task. We're up against a big-time group out of Ohio that claims they have several world records going to the scale today. But we are still site champions for a few more hours, and we hope to defend our title here today."

Backyard Giants

Backyard Giants