- Home

- Susan Warren

Backyard Giants Page 2

Backyard Giants Read online

Page 2

By then, a cool drizzle had begun to fall, and the harvesting crew moved on to the next grower's house. More rain was in the forecast, and there were still a half-dozen pumpkins to load up before the day's end. Ron and Dick swallowed their disappointment and pitched in to help the others.

It was dark by the time all the pumpkins had been loaded into the growers' pickups. The huge orange- and cream-colored lumps loomed high above the truck beds as the growers followed each other to Frerich's Farm, where the weigh-off was to be held the next day. Farm owner David Frerich used a forklift to carry the pumpkins from the trucks to a grassy field. It was a delicate operation that involved spearing the wooden pallet beneath the pumpkin with the forklift's tines, backing away carefully, and then gently lowering the pumpkin to the ground without breaking its tender shell.

Club members Scott Palmer and Fred Macari were thought to have the best shot at winning that year's weigh-off. Fred was a longtime grower who had won the Rhode Island championship the year before and was hoping for a repeat. Scott was one of the club's newest growers. He and his wife, Shelley, had surprised everyone with the boulder that had sprouted in their patch. Scott and Shelley could hardly believe it themselves. They hadn't even managed to grow a 1,000-pound pumpkin before, but this one was estimated to be over 1,300 pounds. It was a bomb, as the big ones were called. The other growers started calling Scott "Palmer the Bomber," which in their broad Rhode Island accents became "Pahma da Bomma."

Each grower, in his turn, clucked and hovered like a nervous hen as the forklift lifted his pumpkin for the move from truck to ground. They worked in the dark in the wet grass by the headlights of the pickup trucks. Scott Palmer went last. As the forklift backed away with Palmer's bomb of a pumpkin raised high on its pallet, there was a grinding noise and the lift gave way, sending the fork and the pumpkin into free fall. An eternity passed in that fraction of a second, and then the lift shuddered to a stop with a jarring crunch, only inches from the ground. The growers froze in horror. In the shocked silence, the same thought raced through everyone's mind: Had the pumpkin cracked? If it had, it was finished. No cracked pumpkins were allowed at the weigh-off. Scott rushed up to exam it, running his hands across the ribs and leaning over to check it underneath. It was still sound. No cracks. As Scott's worried face broke into a relieved smile, the other growers slapped him on the back in glee. It was a good omen. "You broke the truck!" they whooped.

Scott's pumpkin was added to the row of giants lined up in the field to wait their turn at the scale the next day. In the cool, wet night, the pumpkins glowed white and orange and pink, floating in a sea of grass, illuminated by the headlights of the pickup trucks as the growers headed home. It had been a long day, and they were supposed to get started early the next morning.

A heavy rain began later that night and delayed the weigh-off from Saturday to Sunday, and then again to Monday. A cold, light rain was still falling as the competition got underway, dampening the festival atmosphere and cutting the crowd of spectators to less than a quarter of its usual size. Dick still managed to be jovial, but Ron's mood that morning was as gray as the clouds overhead. He was still mourning the loss of his pumpkins, and he was worried about the club. He had been so sure, as the season wrapped up, that they were going to show the world that Rhode Island had been underestimated. Their lineup gave them a better-than-even chance of racking up the highest average weight for the top-io pumpkins of any club in the world. But losing the Wallaces' two 1,300-pound contenders was devastating. Nothing was sure anymore.

Ron did his best to fight off the gloom. He had no time to feel sorry for himself—there was too much to do getting people registered and organized for the weigh-off. Despite the rain delays, 5 2 growers had brought pumpkins to be weighed. A forklift carried the giant pumpkins to the scale one by one. Ron's spirits rallied with the excitement. As club president, he emceed the weigh-off from a platform stage behind the scale. Dressed in a red sweatshirt and faded blue jeans, with a khaki baseball cap pulled low over his eyes, he held a microphone in one hand, engaging the crowd with the easy banter of a game show host and calling out the weights as the growers came forward with each pumpkin.

As the last entries were brought to the scale, Rhode Island grower Steve Sperry surprised everyone with a pumpkin weighing 1,312 pounds. That was almost 150 pounds more than he'd expected, and it was the heaviest he'd ever managed. Then it was Fred Macari's turn. His high, fat, orange pumpkin was bigger than Sperry's, but the digital scale stopped ticking at 1,310.5 pounds. Fred's pumpkin was bigger, but it wasn't heavier.

Massachusetts grower Steve Connolly had created a stir by arriving late, just as he had in 2000 at Topsfield, hauling a small open-bed trailer behind his car. He appeared only moments before the weigh-off began, explaining that his trailer, weighed down by the massive pumpkin, had blown a tire on the road to Frerich's Farm. Whispers swept through the crowd. This could be the winner. The Connolly pumpkin was rumored to weigh more than 1,400 pounds—more than anything the Rhodies had produced.

There is a saying in the giant-pumpkin world that is repeated throughout the year, and especially often at weigh-off time: "The bullshit stops when the tailgate drops." No matter what you think your pumpkin weighs, the scales always have the final word.

The crowd was on edge as Steve Connolly's pumpkin came to the scale. The numbers ticked up . . . past Fred's 1,310.5, past Sperry's 1312 . . . and stopped at 1,333 pounds. That put him in first place, with only Pahma da Bomma's pumpkin left to weigh.

For an instant on that rainy Monday morning of October 10, 2005, in Warren, Rhode Island, as Scott Palmer's pumpkin bomb hit the electronic scale and all eyes were fixed on the red digital numbers zooming upward, past 1,300, past 1,400, some dared to hope Rhode Island might claim the new world record. Why not? Here stood some of the finest growers with some of the biggest pumpkins anywhere. The new world record, set just the week before at 1,469 pounds, seemed within reach. But the red digital numbers slowed, then stopped, at 1,443 pounds. Scott Palmer's pumpkin was bigger than anything else grown in New England that year, big enough to win the Southern New England weigh-off, but it was still 26 pounds shy of the world record.

A quick calculation of the top 10 pumpkins weighed that day revealed an unprecedented club average of 1,173.9 pounds. Even without a contribution from the Wallaces, the Southern New England Giant Pumpkin Growers had seized the title of most successful growing club of all time. The Ohio Valley growers placed second, with their top 10 weighing an average 1,162.2 pounds. And the Massachusetts-based New England club came in third, with a 1,154.6-pound average.

Ron was ecstatic. "That makes us king of the pumpkin world!" he exulted. But the triumph was bittersweet. The club had won without pumpkins from Ron and Dick Wallace. Ron's mind already was racing ahead. The 1,500-pound mark was still hanging out there, waiting to be broken. And once again, with the new year before them, the world record would be anybody's to claim.

Ron and his father had been having too many problems for too long. Ron was tired of the disappointments. Tired of losing pumpkins. It was time for things to change at the Wallace patch. Drastic measures were required to shake themselves out of their losing rut.

What Ron Wallace wanted was really pretty simple. He wanted his name, just once, in that record book. "I know that sometime, before I take that big dirt nap, I'll be a world champion," he said as he looked ahead to the next growing season.

Two thousand and six. A new year. A new chance.

2

Dick and Ron

RON SAT INSIDE the cab of the borrowed dump truck, the engine idling in the farmer's driveway, doing what he usually did when he had time on his hands: he ran the numbers. His mind clicked through them automatically, calculating, measuring, planning. His pumpkin patch was about 60 feet by 125 feet, or about 7,500 square feet. He figured he needed about 20 cubic yards of cow manure, and another 10 cubic yards of chicken manure. The dump truck could carry 8 cubic yards of manure, which

would mean at least four or five trips.

He had to work fast. It was December 3, and already temperatures were dropping to freezing in the middle of the day. Soon the ground would be frozen and there wouldn't be a chance until spring to fix the dirt in their new pumpkin patch—the Quarter Million-Dollar Pumpkin Patch, as his dad called it.

The new garden had been Ron's bold solution. He and his father had made too many mistakes in the old patch. They had poured too many supplements and fertilizers into it, made it too fat and too ripe, a happy breeding ground for giant pumpkins, yes, but also for every bacteria and fungus that might wander in. And plenty had wandered in over the years. So now there was nothing to do but make a fresh start. The problem was, even though Ron's house sat on a five-acre tract of land, there was no convenient place for another patch. The 4,800-square-foot house was heavily landscaped with decks and porches and flower beds. The old patch had sat only about 100 feet from the front door, just a few steps from the sidewalk off the driveway. There was a carriage house next to the main house, and a large red barn near the back of the property with pens for the pony, goats, and rabbits that Ron kept. The lawn was dotted with pine trees and fruit trees. Much of the rest of the property was covered with a large pond and wetlands that meandered through the back. It was beautiful, but it was limiting. There was no place to move a giant-pumpkin patch.

But a plot of seven acres was for sale right next door to his house. Ron had been tempted to buy it when he first learned it was for sale earlier that year, and not just because of the pumpkins. He liked the seclusion in the semirural piece of Rhode Island where he lived. His house was set back perpendicular to the road, shielded by a stand of pine trees. The windows at the front of his house looked straight out over the old pumpkin patch to the property next door, a wooded piece of land filled with scrub brush and pines and crisscrossed with dirt bike trails. If someone else bought the property, they could clear it and build a house smack in his face, ruining his view and his privacy.

The asking price was no bargain, though, and Ron wavered. He wavered right up until they lost their two biggest pumpkins to disease in the old patch. That was the last straw. Ron swallowed hard and plunked down $225,000 for the land, even though he figured he was overpaying. Ron prided himself on being a shrewd businessman, but this wasn't just business. "That's the first time in my life I ever overpaid for something. But how often do you get a chance to buy the land next to your house?" he reasoned.

His dad didn't dispute the logic. Though Ron could rationalize it any way he wanted, Dick said, "I knew better." The truth was, they both wanted that land for a new pumpkin patch. It wasn't a real estate investment; it was a new lease on the Wallace dream of a world record.

Preparations for the 2006 growing season had started as soon as the last 2005 pumpkin rolled off the scale in October. But the deal on the land didn't close until the end of November, leaving the Wallaces precious little time to prepare a new garden. Giant pumpkins are hungry beasts, sucking up vast amounts of soil nutrients each year to fuel their rapid growth. Growers spend most of October and November shoveling in new loads of compost, manure, and other soil supplements to replace the nutrients devoured during the year. The winter gives it all time to break down and blend together before the next spring planting.

Even established gardens demand a lot of work in the fall. But Ron and Dick were starting from scratch. Worse than scratch—three acres of the land Ron bought would need to be cleared and leveled before they could even think about improving the dirt for a new garden. Rome wasn't built in a day, and a world-champion pumpkin patch wouldn't be either. But the Wallaces figured they had at least two weekends.

Early on November 26, a few days after Ron had celebrated his 40th birthday, a horde of Rhode Island pumpkin growers descended on the Wallace place with pickup trucks and tractors and chain saws and axes. It was a chance to pay back all the help and advice and supplies Dick and Ron had handed out to other growers over the years. Like an Amish barn-raising, it also was the rule of the close-knit community. "Everybody helps each other," Ron said. "That's the way it is. We've helped them over the years, and they help us." But, as Dick noted, the gang of growers was tackling something never before attempted in pumpkindom: To get a 7,500-square-foot patch cleared, leveled, amended, and plowed in two weekends of full-blast, all-out, physically exhausting labor.

Temperatures had risen only slightly that morning from the 20-degree predawn chill, but the men warmed up quickly as they set to work. The chain saws roared and buzzed and 80-foot-tall pines began crashing to the ground. Ron had hired an excavator to help with the heavier work. It rolled across the property, its long-armed trowel dipping down and ripping up stumps, shrubs, and other small trees from the ground, then piling them up for burning. While Dick and some of the other growers tended the bonfire, Ron headed out in the dump truck to a nearby chicken farm to get the first load of manure. Others in the group worked on clearing brush and prying large stones from the dirt. Hot coffee warmed their bellies in the morning, and in the afternoon beer warmed their spirits. By the end of that first day, two acres of tumbled raw land, dotted with great piles of manure, stood ready and waiting at the edge of the Wallace compound.

"This hobby doesn't build character; it reveals it," Ron said once. To view a person through a pumpkin prism seems a strange idea at first. But Ron had a point. Growing giant pumpkins, and growing them competitively, is a test of strength, integrity, commitment, and generosity. It asks certain questions: How hard are you able to work? How flexible can you be? Are you willing to share your knowledge and experience to help others—others who will perhaps then go on to beat you? How do you handle disappointment? Are you a quitter?

The Wallaces, perhaps, were better equipped than most to handle the kind of disappointment and hard luck doled out in the pumpkin patch. The family had gone through its share of tough times. Dick Wallace had it tough almost from the time he was born in upstate New York in 1940. His parents were divorced, and Dick had butted heads with more than one stepfather as he grew up. If he had any happy memories from his childhood, he owed them to his grandparents. Dick admired his grandfather, a World War I veteran, lifelong foundry worker, and volunteer firefighter. But he'd had a special bond with his grandmother. "When I was sick, she always took care of me, and when I got into scrapes, as all kids will, Gram used to say, 'Leave him alone. He's just a kid.'"

Dick never used his bumpy start in life as an excuse. Rather, it gave him a sense of confidence and pride. "I did everything on my own," he recalled. "I never depended on my family for anything. I had my rough spots, you bet your life. But I turned out all right."

Dick quit school when he was 17 and joined the U.S. Marine Corps, where he got his first tattoo—a dagger on his forearm. "I thought it made me look tough," he said. To impress the ladies, he got a second one: a wolf wearing a Marine Corps hat that leered from his bicep when he rolled up his sleeve. He met his wife, Cathy, an Italian-American beauty, while on furlough visiting a friend in Rhode Island. They married after he got out of the service in 1963. On their first anniversary, Dick got his third tattoo: two intertwined hearts with "Cathy and Dick" inscribed across them. "If I had it to do over again," he said, "that's the only one I'd keep."

Their sons, Richard and then Ron, were born while Cathy was still finishing nursing school. Dick found a job selling frozen foods door-to-door. As a young man, he was tall and lean and handsome, with neatly groomed jet-black hair and a desire to prove to the world that he could make something of himself. He had an unpretentious charm; he was sincere and cheerful and enthusiastic. Sales took off, but Dick grew to dislike his job. He found himself pulled over a line he wasn't willing to cross: convincing people to buy things he knew they couldn't afford or didn't need. "The problem with sales," he explained, "is that the sale gets to be more important than honesty." So he quit in 1983 and went to work for a local manufacturer of electrical components, where his talent for leadership quickly led to a

job as production superintendent.

Dick made his entry into the world of giant pumpkins—a tale etched in Wallace family lore—with the wide-eyed innocence of a consummate greenhorn. Times were good for Dick and Cathy as they eased into middle age. The kids had grown up and moved out, and they had bought a new house south of Providence with a big backyard. At long last, Dick had room for the big vegetable garden he'd always wanted. As he poked around in a local garden center, he found a packet of seeds for a pumpkin called the Atlantic Giant. He liked the sound of that, and decided to grow a few pumpkin plants along with his tomatoes, bell peppers, and eggplants. He worked diligently on his garden through that summer of 1989. To his delight, his pumpkin plant grew like a demon, sprouting leaves the size of turkey platters and sending thick tendrils branching out across the grass. He'd never seen anything like it. It filled the whole end of Dick's vegetable patch and spawned several pumpkins that swelled as big as beach balls in the heart of his garden.

When the biggest pumpkin finished growing near the end of August, Dick cut it from the vine and carried it to his garage, where he perched it on top of a tire for safekeeping. He'd heard about a pumpkin contest held in October in the town of Collins, New York, 400 miles away, and couldn't resist thinking about his chances at a weigh-off. He didn't really think he could be so lucky as to have a prizewinner his first year . . . but still. It was a big pumpkin.

His grandmother made up his mind. She was living in a nursing home only a few miles from Collins. Going to the weigh-off would give Dick a chance to stop by for a visit. It tickled him to imagine what his gram would say when he showed her the huge pumpkin he'd grown. So six weeks later Dick borrowed the company van and loaded his pumpkin into the back, and he and Cathy set out for what Dick remembers as "four hundred miles of expectations."

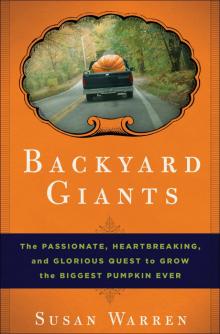

Backyard Giants

Backyard Giants