- Home

- Susan Warren

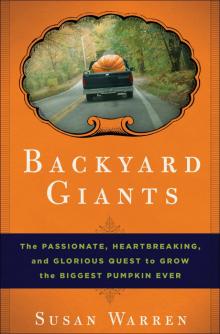

Backyard Giants Page 17

Backyard Giants Read online

Page 17

"Three weeks," Gerry corrected him.

But all was not lost. Gerry's pumpkin, Moonie, was a big pumpkin too. They figured they'd at least win the local weigh-off. "I was hoping for a thousand pounds," said Gerry. Her pumpkin came in at 1,131 pounds, and the Checkons set the new world record after all. "We were just so surprised," Larry said. "Everybody started yelling, 'New world record!' and stuff, and my dad was there too."

"Yeah, Dad cried again that day," Gerry said.

Larry finally got his own world record in 2005, though victory was bittersweet. He was convinced he'd broken through the 1,500-pound mark, the 1,600-pound mark, and even the 1,700pound mark, all in one fell swoop. His pumpkin was a true giant among giants—by far the biggest thing anyone had ever heard of, much less grown. The over-the-top measurements totaled 441 inches, which suggested a weight of more than 1,770 pounds. But in the end, it was a balloon, weighing nearly 300 pounds lighter than expected. That is the puzzle of giant-pumpkin growing, and a supreme frustration of growers. It is a contest of weight, not size. And the OTT measurements only provide an estimate of how heavy a pumpkin is. The bigger giant pumpkins were getting, the more variability there seemed to be, leading to more surprising wins and crushing disappointments.

Larry kept painstaking records of every growing season, recording daily weather conditions such as temperature, rainfall, and sunshine. He made a note whenever he did anything in the patch, from watering to fertilizing or applying fungicide. He measured his pumpkins daily and compared the growth rates to the other conditions he recorded. It was interesting to see how a cold snap slowed growth, a warm spell speeded it up, and a heavy rain sent the pumpkin into overdrive. That's when he realized that pumpkins put on most of their growth at night as they poured the energy they accumulated during the day into the fruit.

"This is a science," Larry said. "I like to make all sorts of observations. I like to know exactly what's happening."

The Checkons had plenty of room to grow as many pumpkin plants as they wanted—8 or 10 like many of the big growers, or even 20-something like the LaRues. But they believed they were better off taking meticulous care of just a few plants. "We believe in quality, not quantity," Larry said.

So he and Gerry grew only two plants apiece. They rarely used sprinklers, preferring to water by hand, spraying a hose beneath the leaves to keep the foliage dry and reduce the chance of fungal infections. They shunned the rigorous fertilizing and pesticide routines other growers followed. When they saw the plants looking a little pale, they fertilized; if bugs showed up, they sprayed. "It's like a tire," Larry said. "If it looks a little flat, you put some air in it. If not, you don't put air in it."

To protect the pumpkin patches from deer and vandals, Larry used his technical skills to rig motion-activated alarms. If the alarm was triggered, an alert would sound over a speaker in their bedroom, and he would jump out of bed and run to the patch to scare away any intruders. This happened a lot, as raccoons, stray cats, and the occasional deer made their way toward the plants. Larry made sure the alarm made a different sound depending on which of the two patches had been violated. That way, he wouldn't waste time running to the wrong patch.

But he knew there was only so much he could do to protect the pumpkins. "No matter what, you're always at the mercy of the weather," he said. And so far in 2006, weather had not been on their side. It had started out cool and wet, with frosts hanging on until the middle of June. Then the temperatures began to swing wildly, from hot to cool.

Despite the erratic weather, both of Gerry's pumpkins were fast out of the gate, estimated at more than 300 pounds apiece. One revved up to gain a brisk 34 pounds a day until the weather turned and a two-day cold snap stopped it in its tracks. By the end of July it had started growing again, but it was only putting on about 24 pounds a day. Gerry was worried it wouldn't pick up its former pace. "I've been doing the up-and-down thing, and I don't like that. I like consistency," she said.

Neither of Larry's pumpkins was growing quite as well as Gerry's. One plant had developed a genetic defect, growing tendrils in places tendrils shouldn't grow. And then the main vine stopped growing. Larry trained a side vine to take its place, but that had set him back two weeks. His second pumpkin was just not growing as fast as he wanted. So far it didn't look like his year.

That was okay. Larry was still busy being world champion. Officially, he was the world's best giant-pumpkin grower, and he was in demand. His phone rang several times a day with questions from other growers around the country. E-mails filled his in-box. Larry knew he had a bull's-eye on his back this year. Everyone in the world was aiming to beat his record. But he was still willing to share anything he knew. In their early growing years, Larry and Gerry had leaned on other pumpkin growers to find out how to grow the giants. They were grateful for the time their mentors spent with them, and they were determined to do the same for other rookies.

Early Monday, July 31, in Massachusetts, Steve Connolly had made his usual dawn inspection of his pumpkins and then turned the sprinklers on in his patch to give the plants a drink before he left for work. The pumpkins all looked good and were growing steadily. At more than 600 pounds, the 1068 was still his runaway star. Steve stepped back and admired his garden in its midsummer glory. It was blanketed in a solid canopy of leaves floating two to three feet above the dirt. The curving tops of yellow and ivory pumpkins peeked above the leaves, accented by bright-blue shade tarps. Sprays of water from the sprinkler caught the sun and arched in shimmering gold through the air. Steve left for work with that idyllic picture still in his head. His garden looked better than it ever had. His 1068 was well on its way to a world record.

That evening, when Steve got home from work, it was cracked open.

Not a big crack. Just a thin, dark line, about two inches long, starting at the base of the stem and running into the shell. It probably would have gone unnoticed by the casual observer. Steve's first hope, his only hope, was that the crack didn't go all the way through to the hollow seed cavity inside the pumpkin. If it did, then air would already have seeped into the sterile, closed internal environment of the pumpkin, introducing microbes, fungi, bacteria, and rot. But if the crack was only skin-deep, there was a chance it would heal over. Steve didn't kid himself. He had feared this exact thing. The 1068 had been growing too fast. It was still growing fast, and as it grew, the crack would just get bigger.

By Tuesday, the crack was longer, wider. By early Wednesday morning, Steve knew it was over. He poked a stick into the black depths of the crevice, now several inches long, and it went all the way through the meat to the void in the center. In the summer heat, it wasn't going to take long for the 1068 to start stinking. So before he left for the office, Steve got his shovel, lifted it high over the pale-orange sphere, and plunged it down with grim resolve. At least this part, ramming the shovel down to crack open the pumpkin, then chopping it up into smaller pieces, was a way of venting frustration. The vine, whose every leaf he had sweated over for three months, was trampled into the soft dirt as he worked. There was no need to be careful anymore. The plant was officially 2006 history. Steve buried the pumpkin pieces in the garden soil as food for next year's plants.

He was deep in thought as he worked. This was no time to whine about what might have been. It was time to start thinking about what he might do to solve the problem next year. This was the exact same place in the garden where a pumpkin had grown like crazy and then blown up last year. There was something about that area of land that was making them grow rampant," he realized. "Next year, I might go in with a different attitude," he said. "I'll water less. Fertilize this spot less. Try to slow down the growth."

Steve finished the job and left for work. Last year he'd lost his largest pumpkin about this same time, and he still finished the season with three pumpkins, weighing 855 pounds, 1,214.5 pounds, and 1,333 pounds. The biggest one had fetched him second place at the Frerich's Farm weigh-off, beaten only by Scott Palmer's 1,443-pounde

r. This year he still had four other plants that needed his care and attention to make it to weigh-off time. "Four others with great potential," he reminded himself. He needed to be thinking about those.

Steve had already pulled off one miracle in his patch. Earlier in July, he'd noticed a foamy, slimy liquid, like half-whipped egg whites, pooling at the base of one of his plants. It was leaking from the stump, soaking into the ground leaving a muddy, foam-flecked goo on top. Steve had treated it with fungicide and set up a fan to blow across the stump, trying to dry it out. And then he had let the main vine grow and keep growing, as long as it wanted. The base of the vine eventually rotted out, but by then Steve had 30 feet of vine growing out beyond the bad spot, providing plenty more roots to feed the pumpkin.

Steve's pumpkin, it turned out, had been among the first to come down with the foaming stump slime that now was beginning to take a heavy toll on the plants of nearly every top grower along the East Coast. The fast-spreading scourge was shaping up to be the 2006 season's dream-killer. For those plants that had survived the flooding rains of spring, the wet year had set up ideal conditions for disease. Fungal spores and bacteria flourished in the water-logged soil, humid air, and warm temperatures. And once a disease got started in a pumpkin patch, it was tough to root it out before all hopes for a world-champion season were destroyed. That had been the Wallaces' perennial sad story. And this year, grower after grower in the soggy eastern United States was coming down with the same mysterious disease.

Jerry Rose and Quinn Werner, two of the Ohio Valley's finest growers, with formidable records of producing 1,000-plus-pound pumpkins, were fighting the slime in their patches. Of Werner's 14 plants, 12 were infected. The problem usually started near the base of the vine, and unless it was stopped, it would creep farther along the vine, rotting the plant from the inside out, slowing the pumpkin's growth and eventually infecting the fruit itself.

Werner's infected plants were still growing a respectable 20 to 30 pounds a day. "But I think they would be doing a little more," he said. "It could be costing me two to eight pounds a day, and that adds up like crazy." His fear was that the problem would get worse.

No one knew what the disease was, though there were many guesses. Some growers believed it was caused by Fusarium or Pythium, two of the notorious plant-rotting fungi that pumpkin growers fought every year. So they hit the infected plants with an assortment of fungicides. Jerry Rose thought it was a bacterial problem, so he'd been using alcohol to try to disinfect the plant.

Otherwise, all that growers could do was drain and clean the infected spot, then set up fans to blow air over the stump to dry it up and try to stop the rot.

It was no cure, but they hoped to slow down the infection long enough to get their pumpkins through the season without too much damage. As a last resort, growers would cut the main vine off the stump to keep the rot from spreading to the rest of the plant. The trend of growing larger plants meant the plants had more-extensive root systems. As Steve Connolly had found out in Massachusetts, the plant could still thrive without its stump, and the pumpkin could still grow. But a damaged plant without a stump seemed to have a poor chance of producing a world-record specimen.

Mother Nature can be heartless, but she's not the only one doling out misfortune in the pumpkin patch. Growers also have to worry about their fellow man. In early August 2005, Randy and Debbie Sundstrom had had four big, beautiful pumpkins growing in their New York pumpkin patch. A couple of them had prizewinning potential. But as they checked on their pumpkins one evening, they noticed the water tank next to the patch, which had been full just that morning, was drained dry. There was a large wet spot on the ground beneath the tank, as if the spigot had been left open. "We knew somebody had been there," recalled Randy.

Then he looked more closely at the plants. The leaves looked wrong. They were a little droopy and were starting to pucker up. "I thought, 'Oh no, something isn't right,'" he said. The Sund-stroms suspected someone had poisoned their plants, and they quickly washed them off as well as they could. But it was too late. By the next morning, the plants were lying flat on the ground, as if a tractor had rolled across them.

The murder of a pumpkin isn't something a grower takes lightly. It gave Randy insight into the phenomenon of temporary insanity. "I wanted to kill pretty bad," he said. The couple called the police to report the crime, to no avail. "Pumpkins?" the police officer said. "You gotta be kidding me!"

Every competition has its scoundrels and cheaters, and giant-pumpkin growing is no exception. Pumpkins are uniquely vulnerable, as they are often left unattended and unprotected in wide-open fields or yards where anyone, under the cover of night or while growers are away at work, can slip in and end a season with a few whacks of a hammer.

Winning is a powerful tonic. Overnight, a world-champion grower becomes a pumpkin maharishi, with other growers reaching out to tap their skills and wisdom. Congratulatory e-mails and phone calls pour in from pumpkin peers around the world. Television and newspaper reporters request pictures and interviews with the person who has just grown the biggest pumpkin in the world. Even television talk shows come calling—past winners have traveled to New York to appear (or have their pumpkins appear) on Live with Regis and Kathie Lee, The Martha Stewart Show, and the Late Show with David Letterman.

After the first rush of attention dies down, the world champion gets a yearlong victory lap to revel in the crown. The official presentation of the orange jacket is made in March at the annual growers' conference in Niagara Falls. The champion is invited to speak at grower seminars and pumpkin events. They're asked again and again to—just one more time—tell the story of how they did it. And even after the baton is passed to a new champion, winning growers get to claim the title for life, their name forever coupled with their world title.

Even at the local level, where growers compete in front of friends and family, egos are on the line and the desire to beat a neighbor can sometimes overtake good sense.

The Sundstroms had only been growing a few years, but they'd been extraordinarily successful, winning local weigh-offs and unseating other past champions. The couple had no room for a giant-pumpkin patch at their home at the foot of the Catskill Mountains, west of New York City. So they made a patch on a vacant lot owned by Debbie's parents about 15 minutes away. The lot had no utilities, so they kept a 3,800-gallon water tank in a trailer, filled it with water each week, and parked it at the patch to water their plants.

After the sabotage incident, the Sundstroms sent in plant samples to a laboratory for testing. The lab confirmed that weed killer had been sprayed on their pumpkins. They could never prove it, but they suspected a jealous grower of trying to knock them out of the year's competition—though Randy didn't like to dignify the vandal by calling him a grower. "If he was a true pumpkin grower, he would know how hard you work to get that pumpkin successfully to the weigh-off," Randy said, noting that a true grower "would never do something like that."

Later in the year, the house across the street from their patch went up for sale, and the Sundstroms bought it and moved in so they could keep a closer eye on their pumpkins. They installed lights and surveillance cameras on the lot's driveway and along the pathways of the garden. And they recruited spies from the neighborhood to keep an eye on things while they were at work during the day. "We have everybody driving by our garden watching out for us," Randy said.

Sabotage isn't the only way to cheat. With weight being the determining factor, the pumpkin's hollow core presents a tantalizing opportunity to bulk up a pumpkin from the inside out. Growers often joke about filling their pumpkin with sand or some other heavy substance to increase its weight. They laugh over the notion of pumpkins filled with cement. They call them "white dwarfs," like the collapsed stars that are among the densest objects in the universe.

But the jokes aren't that far away from reality. Years ago, a grower on the East Coast cut a small hole in his pumpkin, filled it with water, and then plugged the

hole so that it was nearly invisible. The trick was discovered after the pumpkin sloshed as it was carried to the scale and suspicious judges cut a hole in it. As Dick Wallace tells it, "The water gushed out like diarrhea out of a cow's behind."

The trick inspired the rule disqualifying damaged pumpkins from competition. Bruises and scars and even some soft spots are allowed, but there can be no holes or cracks, no matter how tiny, that penetrate through the shell to the seed cavity. Through the growing season, competitors are given tremendous leeway in their pursuit of the biggest, heaviest pumpkin. There is no limit to the kinds of fertilizers or additives that can be tried, and no restrictions on the growing techniques that can be used. But once the pumpkin is cut from the vine, it's got to be ioo percent pure fruit; no foreign substances are allowed anywhere near it, not even vegetable oil to give the skin a shine.

That decree has caused much heartbreak among honest growers who have had a pumpkin disqualified when it developed a minuscule fracture right before a weigh-off. But it's also led to a new dedication to good sportsmanship in the hobby.

Ohio Valley pumpkin grower Dave Stelts was watching broadcasts of the 2004 Winter Olympics when television commentators reminded viewers of the story of the bobsledders in the 1964 games in Innsbruck, Austria. British bobsledders Tony Nash and Robin Dixon had broken an axle bolt on their two-man bobsled before their final run. Their Italian rivals loaned them the part. The British team fixed their sled and went on to win the gold medal, while the Italian team that had helped them came in third. The incident went down in history as one of the most inspiring moments ever in sports competition.

Backyard Giants

Backyard Giants