- Home

- Susan Warren

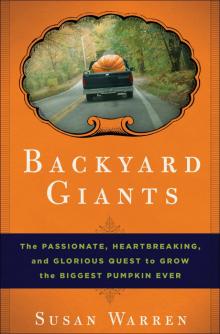

Backyard Giants Page 12

Backyard Giants Read online

Page 12

Before Ron strapped on the sprayer, he bent down to lace up his father's latest invention—a pair of garden walking shoes. The boards they'd laid down between the plants didn't always go where Ron wanted to go, so he had been dragging a plank along with him through the garden, laying it down and walking on it to reach a vine that needed pruning or a pumpkin that needed pollinating. But that was difficult to do when he was spraying the plants and needed to move about more freely. So Dick's inspired solution was to design a snowshoe-style garden shoe for Ron. He'd sawed a piece of plywood into i7-by-6-inch boards and then screwed a pair of Ron's old sneakers into the center of the boards. Then he nailed a shorter, wider board beneath the first. It looked like the shoes had wings, so Dick called his new invention "wingtips." The shoes distributed Ron's weight over a larger area, making it less damaging to walk in the patch. "They look funny as hell," Dick admitted. They weren't easy to walk in, either: The board stuck out several inches around the shoes, and Ron had to swing his legs wide in a high-stepping gait to keep from tripping. But Ron wore the shoes because they worked, and of course, he wore them because his father made them.

Strapped in, laced up, Ron was ready for action. He stood at the edge of his new pumpkin patch, his sprayer mounted on his back, his wingtips planted firmly in the earth, looking like an astronaut preparing to leave the ship on a space walk. His gaze swept over the patch, making a critical survey of the plants. The patch looked picture-perfect. The plants were huge—each one was 15 to 20 feet long and 25 feet across at the base. They were planted back to back, with the stumps in a row down the middle of the patch, and the plants were growing out in perfect Christmas-tree shapes, their triangular forms pointing toward the edges of the garden like the prows of battleships lined up at a dock.

Despite the record rains, the garden dirt still looked fluffy from the hand-tilling Ron had done around the vines. Ron and his dad kept the dirt weed-free in a five-foot zone around each plant. Small weeds were sprouting in the spaces in-between, but they didn't care about that anymore. Ron and Dick were determined to work smarter, not just harder. That included cutting down on some of the intensive labor, such as weeding every square inch of garden. In their former, more-fanatical days, Ron and Dick had been meticulous about keeping the whole patch weed-free. "But it's not a beauty contest," Ron said. As long as the weeds were kept away from the plants' root zones, the rest didn't matter as much.

Only one large weed was left growing right in the middle of the patch. It was a two-foot-tall Cleome, or spider flower, crowned with delicate clusters of pale-violet blooms. Dick had convinced Ron to leave it alone as long as it was flowering, and it stuck out oddly, though prettily, from the neatly groomed greenery of the surrounding pumpkin plants.

Ron viewed all this with a critical eye. He saw the good—the plants were the healthiest he'd ever grown. But he also saw all the work that still needed to be done. Steady rains had kept him out of the patch for two days, and the vines were already getting out of control.

They'd grown two feet in those two days, and it was crucial to get them covered with dirt as quickly as possible so they could begin forming the root system that would pump more energy into the growing pumpkin. The root system along the vine also acted as a kind of insurance policy. If anything happened to injure the plant farther back toward the base, it could still survive. Ron and his dad had been able to grow pumpkins as big as 1,200 pounds after losing the stump to rot, thanks to the plant's auxiliary root system.

With the brownish-greenish-black compost tea sloshing in the tank on his back, Ron stepped into the pumpkin patch, fired up the sprayer's engine, and blasted a fine, drifting spray that soaked the plant leaves and dripped down into the dirt below. While Ron sprayed the plants, Dick wandered back to the Pumpkin Shack. The Wallace carriage house made the perfect headquarters for the Southern New England growing club. It had been renovated into a simple, one-room cottage with plywood walls and a concrete floor, a small kitchen, a bathroom, and a refrigerator stocked with beer. Pumpkin photographs, dozens of ribbons and plaques, and framed copies of Dick's pumpkin cartoons covered the walls, along with a hot-pink poster of the rock band KISS. "It's a seventies thing," Dick explained.

On the kitchen counter, Dick had laid out a stack of tan T-shirts imprinted with the new club logo he'd drawn. It was a simple map of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, with a bright-orange giant pumpkin in one corner and the club initials above. Dick was the official club artist. Over the years he'd composed a thick portfolio of one-panel cartoons lampooning the life of giant-pumpkin growers. He called them his "PumpkinToons," and had some printed on T-shirts and caps that were popular among growers.

Dick planned to hand out the T-shirts at the club meeting that would begin shortly, along with large white lapel buttons he'd had made to commemorate the Southern New England Giant Pumpkin Growers 2005 weigh-off championship. The directors and some of the Rhode Island members tried to get together at least once a month to discuss club business, and that night they needed to review prize money for the October weigh-off. Some snacks and paper plates and plastic utensils were already laid out on a table for the meeting.

Assured that all was in order, Dick took a seat in a lawn chair on the porch to rest for a few minutes before the club members arrived. Despite the terrible weather, Dick was well satisfied with the way the season was going. Their plants seemed to have caught up, and they were right on schedule for pollinating. Of the 10 they were growing, Dick felt good about 8. The 2 others, including the 1354 Checkon, were dragging. "But who knows. We could still get our best pumpkins out of them," he said. He was still betting on their 1068s, though. Out of the 5, he felt sure they could get at least 3 competitive-sized pumpkins.

As Dick watched Ron work in the patch, Ken Desrosiers, the BigPumpkins.com Webmaster, arrived for the evening's club meeting. He was one of the club's directors, and he'd come straight from his office in Connecticut. He walked over to talk with Ron, who was finishing spraying the plants, then the two men joined Dick on the porch. Ken drew up a chair and sat down, declining Dick's offer of a beer. "No thanks. I have a long drive home in the dark," he said. Ken had a wife and two young children to pull him back to firm ground whenever the undertow of pumpkins got too strong.

Ron puttered around the porch, not yet able to sit down and relax. He checked the dirt inside the flowerpots arranged along the edge of the porch, then fetched a green plastic watering can to give them a drink. The conversation drifted inevitably to pumpkins and the topic on everyone's mind: pollination.

The time to pollinate the baby pumpkins had finally arrived—a pivotal moment in the growing year. The season started when the plants went into the ground in early May, but pollination was the starting gun for the race that really counted. It was early July, and most of the plants were finally big enough and mature enough to have baby pumpkins nestled beneath their female blooms ready for fertilization. Left unfertilized, the tiny pumpkins would simply shrivel up after a week or so and fall off. So there would be no giant pumpkins without proper pollination, and that meant joining the male and the female flowers together in carefully orchestrated intercourse.

Pumpkin plants have both male flowers, which provide the pollen for fertilization, and female flowers, which grow the pumpkin. So a female (mother) can be pollinated with a male (father) from the same plant. But growers usually like to mix up the genetics by pollinating the female flower with a male flower from an other plant—a process called cross-pollination, or "crossing." Every grower hoped to have his name attached to the next "killer cross"—pumpkin jargon for a genetic matchup between pumpkin plants that would take the giants another step up the evolutionary scale. The 1068 Wallace, for instance, was the result of a killer cross between an 845 Bobier female and an 898 Knauss male.

Growers hand-pollinated the female flowers on every plant to control the genetic parentage and to make sure each selected female was thoroughly fertilized. Ultimately, just one pumpkin would

be grown on each plant so that all the energy would be poured into blowing up that pumpkin as big as possible. But growers started out by pollinating several females on each plant. Sometimes the pollinations wouldn't "take," and the embryonic pumpkin would abort. Some baby pumpkins would grow faster than others. Some would have a better shape. Some would be in a better position on the vine. All those things were carefully weighed and debated by every grower at pollination time.

"The weirdest thing happened to me on one of my plants," Ken Desrosiers was saying to Dick. He worried that the rainy weather had messed up his pollination chances on one of the two plants he was growing. "I'm twelve feet out on the main, and the females were getting ready to go, and all of a sudden they shriveled up on me. They never even opened. That's the first time that's ever happened."

"Yeah," said Dick, with a knowing nod. "If you look at the flower, and the tip looks like it's kind of burned, like it's glued together . . . that was from all that rain."

"I would have been ready to go on July 1 with that plant," said Ken. "But now I just pollinated one on the other plant, the 1173, yesterday, on July 4." Ken was a fairly new grower, and he was still figuring out what worked best. "I used to pollinate everything. I had two plants and I'd pollinate forty flowers," he mused.

"We were talking about that the other day," Ron said, pausing with his watering can tilted over one of the flowerpots. "I said, 'Dad, remember that year when we did one hundred and twenty pollinations?'"

"Oh yeah. We had like fifteen pumpkins pollinated on each plant," Dick recalled. "We were culling three-hundred-pound pumpkins until we said, 'What the hell are we doing here?' Getting hernias! The thing is, the more you do this hobby, the more you learn that sometimes less work is better."

Soon, the other club members began to arrive for the meeting, their trucks filling the driveway and spilling over into the grass. Ron had called the meeting to discuss the club's budget and other administrative matters, but in the soap-opera world of giant pumpkins, the only thing the growers gathered in the Pumpkin Shack really wanted to talk about was who was pollinating whom.

Fifteen-year-old Alex Noel, who had been growing pumpkins since he was 11, was dropped off at the meeting by his dad. Ron tried to bring him into the conversation. "Alex, how're your plants doin'?"

"Doing good," Alex answered. "Pollinated the 1068 this morn-ing."

"What did you put into it?"

"The 1058."

"Oh, that's a nice choice," Ron said approvingly. "The 1058 is bomb-proof. It's not known for splits. Long and wide. It's not known for color, but it averages 10 percent over the charts. That's a nice cross."

"I don't care about color at all," said Alex.

"That's like me—I'm not a color guy at all," Ron agreed.

Peter Rondeau, who lived only a few miles from the Wallaces, asked Ron if he could have some male flowers off one of their plants to pollinate one of his females the next morning. "I'll cut them and take them home and put them in the fridge," he told Ron.

Ron snapped to attention. "Why are you putting them in the fridge?"

Peter looked up, startled. "I don't know."

"Those plants you're taking them from aren't in the fridge," Ron pointed out. "Leave 'em at room temperature. Put 'em in a little bit of warm water, that way they open up in the morning. You want something that's fresh and open." Peter nodded, a disciple eager to learn.

Growers decide on the seeds they'll plant each year mainly based on which ones they think will grow the biggest pumpkin. But they're also constantly thinking about the genetic matchmaking game. Seed decisions are sometimes influenced by which plant a grower wants to cross with another. The male doesn't affect the growth of the current season's pumpkin; it only matters for the seeds that will grow inside that pumpkin, which will carry the combined male and female genes into the next generation.

Before the meeting started, Ron and Dick took the club members on a tour of their new patch. The growers strung out in different groups as they walked slowly around the perimeter of the garden. The seaweed-infused compost tea had left behind a slightly fishy odor, like at the beach. Ron and Dick had already pollinated several pumpkins, and two others would be ready to go the next morning. Ron pointed out a leaf stalk crowding one of the baby pumpkins he planned to pollinate the next day. "I don't like that leaf rubbing up against the pumpkin, so I'm going to cut it," he told Joe Jutras.

"I'd leave it," said Joe. "I leave it if it's on top. If it's on the bottom, you have to take it off."

"I'll take it right off," Ron persisted. "I want to be wide open there."

"I don't know," said Joe. "You guys grow a lot of friggin' bird-baths." A birdbath was grower slang for a pumpkin that tipped over on its stem so that the opposite, "blossom end" was pointing up. The blossom end often sank in to form a concave spot, like a birdbath. It wasn't a desirable shape, and Ron didn't much like being reminded of their track record.

"That leaf has nothing to do with birdbaths," he argued. "Why would a leaf have anything to do with a birdbath?"

"I don't know. Maybe it's nothing . . ."

"I don't know" was Joe's polite way of saying, "I think you're wrong." A lifelong gardener, he had more experience and was at least as knowledgeable as the Wallaces when it came to growing the giants, but he was quieter about it. Still, he didn't hesitate to voice his opinion, and when he did, all the growers paid attention, Ron and Dick included.

Ron and Joe carried on discussing the characteristics of each plant as the other growers spread out around the patch. Ron was proud to show off his plants, but he was anything but confident. "I still don't know if this soil is capable of growing a truly world-class pumpkin the first year," he said to Joe. "That's asking an awful lot—to balance it, get it corrected, and get it rolling the first year. I mean, you can grow a plant, and so far the plants haven't suffered or anything, but to grow thirty or forty pounds a day . . . I guess we're going to find out in a couple of weeks."

The growers arrived at the spot where Ron and Dick had planted Joe's 1225 orange beauty. Since they planned to pull it up as soon as they'd used its male flowers, the plant hadn't received the same care as the other plants, and it looked straggly and weak. "There's Joe's 1225," one grower pointed out, teasing Joe about the shabby treatment of his prized pumpkin seed. "They're really taking care of it, I tell you. Grown for pollen. We get no respect."

Joe's mouth tilted in a good-natured grin. "Prettiest pumpkin I ever grew," he said. "True orange."

"Just strippin' it for parts, like a junk car," the grower said, twisting the knife.

Ken Desrosiers noticed the giant weed growing in the middle of the pumpkin patch. "What's that?" he asked Ron.

"Oh, that's a Cleome. My father found it growing there, so he wanted to keep it. I'll pull it out as soon as the main vine finishes growing."

Joe jumped to the flower's defense. "It won't bother anything," he said.

"It'll be gone," said Ron, closing the subject.

Ron rounded up everyone and hustled them back to the Pumpkin Shack to grab a bite to eat before the meeting started.

Cathy Wallace dropped in to say hello as everyone filled their plates with calzones and spinach pies. She had just come out of the hospital again, after another lung infection, but on this evening she looked fresh and youthful in a white blouse and pale denim overalls. She stood near the door to the club headquarters, greeting the growers, most of them old friends.

"I missed the Fourth of July picnic at Ronnie's club," she said wistfully. "The first year we've ever missed it." She wasn't complaining, just remarking on it. "There's always next year," she said.

Cathy was feeling weak and tired much of the time lately. Mostly, though, she worried about how her illness was affecting Ron and Dick and their granddaughter, Rene. Whenever Cathy was sick, Dick would get to feeling blue too. Ron was constantly fretting over what he could do for his mom to make her more comfortable. Cathy had accidentally dialed his cell phone the ot

her day when she meant to call someone else. She canceled the connection, but not before her name popped up on Ron's caller ID. He called her right back. "Mom, did you call me?" "No, Ronnie," she said. "I was trying to call someone else." "Okay," he said. "But are you sure you don't need anything? Are you sure there isn't something I can do for you?" Cathy smiled a mother's sad smile as she told the story. She was touched by her son's concern, but hated that she was the cause of his worry. "When Ronnie was a little boy, he was never one for a lot of hugs or kisses," she said. "But now he hugs me and tells me he loves me all the time."

The Southern New England growers were in high spirits as Ron convened the meeting at 6 P.M. sharp. Most of their plants had made it through the worst of the weather. They were excited to be starting the next phase of the season, and every grower was eager to share stories of what they had going and what they planned to make of it. The growers grabbed lawn chairs off the porch and lined them up against the wooden walls inside the Pumpkin Shack. Scott Palmer showed up late and stood just outside the open door on the porch, smoking a cigarette.

Ron sat in front of the group in a white lawn chair, one bare ankle crossed over his knee as he chewed the end of a pen and ran his eyes down a typewritten agenda he'd prepared. The twittering songbirds had given way to the noises of crickets and frogs living down at the Wallaces' pond. But all that was drowned out by the raucous laughter and numerous one-liners being tossed back and forth. The men talked louder and louder to be heard in a steadily rising tide of noise. This was no orderly business session. It was more like calling a meeting in a saloon full of rowdy cowboys fresh off the Chisolm Trail.

Backyard Giants

Backyard Giants